- Management Reference Guide

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Strategic Management

- Establishing Goals, Objectives, and Strategies

- Aligning IT Goals with Corporate Business Goals

- Utilizing Effective Planning Techniques

- Developing Worthwhile Mission Statements

- Developing Worthwhile Vision Statements

- Instituting Practical Corporate Values

- Budgeting Considerations in an IT Environment

- Introduction to Conducting an Effective SWOT Analysis

- IT Governance and Disaster Recovery, Part One

- IT Governance and Disaster Recovery, Part Two

- Customer Management

- Identifying Key External Customers

- Identifying Key Internal Customers

- Negotiating with Customers and Suppliers—Part 1: An Introduction

- Negotiating With Customers and Suppliers—Part 2: Reaching Agreement

- Negotiating and Managing Realistic Customer Expectations

- Service Management

- Identifying Key Services for Business Users

- Service-Level Agreements That Really Work

- How IT Evolved into a Service Organization

- FAQs About Systems Management (SM)

- FAQs About Availability (AV)

- FAQs About Performance and Tuning (PT)

- FAQs About Service Desk (SD)

- FAQs About Change Management (CM)

- FAQs About Configuration Management (CF)

- FAQs About Capacity Planning (CP)

- FAQs About Network Management

- FAQs About Storage Management (SM)

- FAQs About Production Acceptance (PA)

- FAQs About Release Management (RM)

- FAQs About Disaster Recovery (DR)

- FAQs About Business Continuity (BC)

- FAQs About Security (SE)

- FAQs About Service Level Management (SL)

- FAQs About Financial Management (FN)

- FAQs About Problem Management (PM)

- FAQs About Facilities Management (FM)

- Process Management

- Developing Robust Processes

- Establishing Mutually Beneficial Process Metrics

- Change Management—Part 1

- Change Management—Part 2

- Change Management—Part 3

- Audit Reconnaissance: Releasing Resources Through the IT Audit

- Problem Management

- Problem Management–Part 2: Process Design

- Problem Management–Part 3: Process Implementation

- Business Continuity Emergency Communications Plan

- Capacity Planning – Part One: Why It is Seldom Done Well

- Capacity Planning – Part Two: Developing a Capacity Planning Process

- Capacity Planning — Part Three: Benefits and Helpful Tips

- Capacity Planning – Part Four: Hidden Upgrade Costs and

- Improving Business Process Management, Part 1

- Improving Business Process Management, Part 2

- 20 Major Elements of Facilities Management

- Major Physical Exposures Common to a Data Center

- Evaluating the Physical Environment

- Nightmare Incidents with Disaster Recovery Plans

- Developing a Robust Configuration Management Process

- Developing a Robust Configuration Management Process – Part Two

- Automating a Robust Infrastructure Process

- Improving High Availability — Part One: Definitions and Terms

- Improving High Availability — Part Two: Definitions and Terms

- Improving High Availability — Part Three: The Seven R's of High Availability

- Improving High Availability — Part Four: Assessing an Availability Process

- Methods for Brainstorming and Prioritizing Requirements

- Introduction to Disk Storage Management — Part One

- Storage Management—Part Two: Performance

- Storage Management—Part Three: Reliability

- Storage Management—Part Four: Recoverability

- Twelve Traits of World-Class Infrastructures — Part One

- Twelve Traits of World-Class Infrastructures — Part Two

- Meeting Today's Cooling Challenges of Data Centers

- Strategic Security, Part One: Assessment

- Strategic Security, Part Two: Development

- Strategic Security, Part Three: Implementation

- Strategic Security, Part Four: ITIL Implications

- Production Acceptance Part One – Definition and Benefits

- Production Acceptance Part Two – Initial Steps

- Production Acceptance Part Three – Middle Steps

- Production Acceptance Part Four – Ongoing Steps

- Case Study: Planning a Service Desk Part One – Objectives

- Case Study: Planning a Service Desk Part Two – SWOT

- Case Study: Implementing an ITIL Service Desk – Part One

- Case Study: Implementing a Service Desk Part Two – Tool Selection

- Ethics, Scandals and Legislation

- Outsourcing in Response to Legislation

- Supplier Management

- Identifying Key External Suppliers

- Identifying Key Internal Suppliers

- Integrating the Four Key Elements of Good Customer Service

- Enhancing the Customer/Supplier Matrix

- Voice Over IP, Part One — What VoIP Is, and Is Not

- Voice Over IP, Part Two — Benefits, Cost Savings and Features of VoIP

- Application Management

- Production Acceptance

- Distinguishing New Applications from New Versions of Existing Applications

- Assessing a Production Acceptance Process

- Effective Use of a Software Development Life Cycle

- The Role of Project Management in SDLC— Part 2

- Communication in Project Management – Part One: Barriers to Effective Communication

- Communication in Project Management – Part Two: Examples of Effective Communication

- Safeguarding Personal Information in the Workplace: A Case Study

- Combating the Year-end Budget Blitz—Part 1: Building a Manageable Schedule

- Combating the Year-end Budget Blitz—Part 2: Tracking and Reporting Availability

- References

- Developing an ITIL Feasibility Analysis

- Organization and Personnel Management

- Optimizing IT Organizational Structures

- Factors That Influence Restructuring Decisions

- Alternative Locations for the Help Desk

- Alternative Locations for Database Administration

- Alternative Locations for Network Operations

- Alternative Locations for Web Design

- Alternative Locations for Risk Management

- Alternative Locations for Systems Management

- Practical Tips To Retaining Key Personnel

- Benefits and Drawbacks of Using IT Consultants and Contractors

- Deciding Between the Use of Contractors versus Consultants

- Managing Employee Skill Sets and Skill Levels

- Assessing Skill Levels of Current Onboard Staff

- Recruiting Infrastructure Staff from the Outside

- Selecting the Most Qualified Candidate

- 7 Tips for Managing the Use of Mobile Devices

- Useful Websites for IT Managers

- References

- Automating Robust Processes

- Evaluating Process Documentation — Part One: Quality and Value

- Evaluating Process Documentation — Part Two: Benefits and Use of a Quality-Value Matrix

- When Should You Integrate or Segregate Service Desks?

- Five Instructive Ideas for Interviewing

- Eight Surefire Tips to Use When Being Interviewed

- 12 Helpful Hints To Make Meetings More Productive

- Eight Uncommon Tips To Improve Your Writing

- Ten Helpful Tips To Improve Fire Drills

- Sorting Out Today’s Various Training Options

- Business Ethics and Corporate Scandals – Part 1

- Business Ethics and Corporate Scandals – Part 2

- 12 Tips for More Effective Emails

- Management Communication: Back to the Basics, Part One

- Management Communication: Back to the Basics, Part Two

- Management Communication: Back to the Basics, Part Three

- Asset Management

- Managing Hardware Inventories

- Introduction to Hardware Inventories

- Processes To Manage Hardware Inventories

- Use of a Hardware Inventory Database

- References

- Managing Software Inventories

- Business Continuity Management

- Ten Lessons Learned from Real-Life Disasters

- Ten Lessons Learned From Real-Life Disasters, Part 2

- Differences Between Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity , Part 1

- Differences Between Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity , Part 2

- 15 Common Terms and Definitions of Business Continuity

- The Federal Government’s Role in Disaster Recovery

- The 12 Common Mistakes That Cause BIAs To Fail—Part 1

- The 12 Common Mistakes That Cause BIAs To Fail—Part 2

- The 12 Common Mistakes That Cause BIAs To Fail—Part 3

- The 12 Common Mistakes That Cause BIAs To Fail—Part 4

- Conducting an Effective Table Top Exercise (TTE) — Part 1

- Conducting an Effective Table Top Exercise (TTE) — Part 2

- Conducting an Effective Table Top Exercise (TTE) — Part 3

- Conducting an Effective Table Top Exercise (TTE) — Part 4

- The 13 Cardinal Steps for Implementing a Business Continuity Program — Part One

- The 13 Cardinal Steps for Implementing a Business Continuity Program — Part Two

- The 13 Cardinal Steps for Implementing a Business Continuity Program — Part Three

- The 13 Cardinal Steps for Implementing a Business Continuity Program — Part Four

- The Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL)

- The Origins of ITIL

- The Foundation of ITIL: Service Management

- Five Reasons for Revising ITIL

- The Relationship of Service Delivery and Service Support to All of ITIL

- Ten Common Myths About Implementing ITIL, Part One

- Ten Common Myths About Implementing ITIL, Part Two

- Characteristics of ITIL Version 3

- Ten Benefits of itSMF and its IIL Pocket Guide

- Translating the Goals of the ITIL Service Delivery Processes

- Translating the Goals of the ITIL Service Support Processes

- Elements of ITIL Least Understood, Part One: Service Delivery Processes

- Case Study: Recovery Reactions to a Renegade Rodent

- Elements of ITIL Least Understood, Part Two: Service Support

- Case Studies

- Case Study — Preparing for Hurricane Charley

- Case Study — The Linux Decision

- Case Study — Production Acceptance at an Aerospace Firm

- Case Study — Production Acceptance at a Defense Contractor

- Case Study — Evaluating Mainframe Processes

- Case Study — Evaluating Recovery Sites, Part One: Quantitative Comparisons/Natural Disasters

- Case Study — Evaluating Recovery Sites, Part Two: Quantitative Comparisons/Man-made Disasters

- Case Study — Evaluating Recovery Sites, Part Three: Qualitative Comparisons

- Case Study — Evaluating Recovery Sites, Part Four: Take-Aways

- Disaster Recovery Test Case Study Part One: Planning

- Disaster Recovery Test Case Study Part Two: Planning and Walk-Through

- Disaster Recovery Test Case Study Part Three: Execution

- Disaster Recovery Test Case Study Part Four: Follow-Up

- Assessing the Robustness of a Vendor’s Data Center, Part One: Qualitative Measures

- Assessing the Robustness of a Vendor’s Data Center, Part Two: Quantitative Measures

- Case Study: Lessons Learned from a World-Wide Disaster Recovery Exercise, Part One: What Did the Team Do Well

- (d) Case Study: Lessons Learned from a World-Wide Disaster Recovery Exercise, Part Two

This segment was written by Tom Cutting.

The end of the year is coming and IT budgets must be spent or swept back into profit and loss columns. Toward the end of the year, IT projects that are finishing under budget are dumping dollars back into their department coffers while funds that have been on reserve are being released. As a result of this "found" money, department heads are pressuring project managers to complete new projects by the end of the year without additional resources. If this is the norm for your workplace you aren't alone. To avoid this end-of-year crunch, you, as the project manager, need to develop manageable project schedule and use it to track and report resource availability throughout the year. This will allow you to avoid the year-end budget blitz by returning unnecessary funds earlier and give you the ability to communicating resource over-allocation at the end of the year.

This two-part article discusses how to develop a detailed project schedule, track progress, and communicate resource usage. Part one focuses on the five keys to building a manageable project schedule, while part two outlines four critical resource-tracking steps and how to use your plan to communicate availability to your management. By actively maintaining your schedule, you will be able to accurately forecast the needed time and personnel throughout the life of the project and return unneeded funding throughout the year. Unfortunately you will be able to hold back the flood of last-minute funding or the additional time-pressured projects that accompany them. But you will be able to divert some pressure by demonstrating a realistic picture of available resources with your detailed schedule.

Five Keys to Building a Manageable Schedule

There is a belief that projects that end up way under budget are better managed than those that are on or even slightly above budget. In reality, "under budget" usually means "over estimated." To avoid over-estimating your budget, project managers must develop a manageable project schedule by following five key steps:

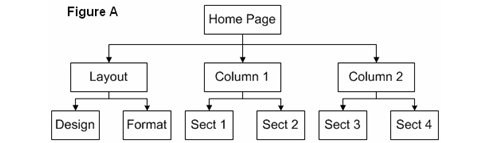

- Make it deliverable-based. Before you open your scheduling tool

take the time to define what it is you are developing. Begin with the end

product and, with your team, identify the smaller, tangible pieces, or

deliverables, needed to get there. This process is known as developing a work

breakdown structure (WBS). As a simple example, consider customizing your YAHOO!

home page. The WBS would look like figure A.

The deliverables for this project are the design, format, and sections one through 4. When these interim products are put together, the end result is a new home page. Further refinement would begin to define activities and tasks such as analyzing backgrounds, reviewing color palette, and selecting a design, which are tasks that would be handled in step 2.

- Identify tangible tasks. With the deliverables identified, continue

to break down the WBS until you have a list of tasks for each deliverable that,

when performed, results in the development of the interim product. Tangible

means that whoever is assigned to the task is able to understand what is

involved to complete it. From our example, tasks for each column section would

include picking a topic for each column section; reviewing and selecting

content; and publishing content to the page. As a general rule of thumb, keep

tasks to a maximum of two weeks. The human mind can quickly grasp what can be

accomplished for an 80-hour task or within a two-week time period.

All activities and tasks must form a part of one of the deliverables. Collectively, the deliverables will constitute your project scope. Anything not associated with these deliverables would then be out of scope. In our example, training your family to navigate the new home page is out of scope, so it shouldn't appear in the schedule.

You do not necessarily have to track at the lowest task level. You can group several smaller tasks into work products for time tracking. However, it is important that individual tasks be made available to the team as checklists to ensure all steps are completed and estimates to complete (ETC) accurately reflect the remaining effort.

- Tag tasks with logical dependencies. Project planning tools like Microsoft Project and Primavera have auto-scheduling features. Every time you press the enter key, the tool recalculates the end dates based on resource availability and dependencies. Without logically setting the predecessors and successors in your schedule, the tools cannot perform their jobs effectively. It isn't necessary to tag every task with a dependency, but phase and activity levels are good candidates.

- Estimate accurate hours and durations. For each task, estimate the

number of hours it would take a single individual to complete it. You

haven't added specific resources to the schedule yet, but you probably have

a good idea of the skill level for the tasks. Take that into account as you

estimate. If your schedule groups multiple tasks into work products, summarize

the estimated hours from the actual task list.

The scheduling tool has already calculated an end date based on an eight-hour day, five-day week, but you need to add reality to the mix. No one, over an extended period of time, accomplishes an eight-hour task in a single day without being at working for 10 hours. Interruptions, time and status reporting, and meetings disrupt productivity. Add to this list vacations, sick time, and training and productivity drops to about 80% maximum over the course of the year. The temptation is to adjust the resource availability to 80%. Avoid it.

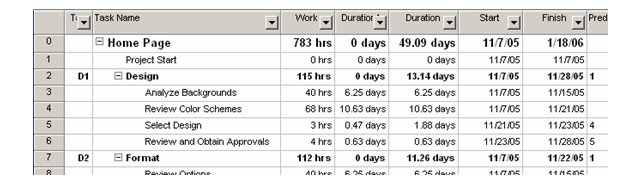

Instead, adjust the duration of each task to reflect the time it would take a single resource to accomplish it. For example, a 40-hour task takes approximately 6.25 days to complete. You may be more pessimistic and say that a 40-hour task takes up to two weeks (10 days). Not altering the resource availability allows the scheduling tool to assign each resource multiple tasks totaling 40 hours of work for the week, which is what you want. Everyone is still expected to work a full week, but the full week won't be spent on a single task. For information on how to automate an 80% productivity factor in Microsoft Project, see the "Bonus" section at the bottom of this article.

Don't develop the hours and duration estimates in a vacuum. Involve the team to get realistic values and timeframes. This will create buy-in from them and increase their confidence in achieving the ultimate goal. With that said, you will always have to look out for padding and adjust the schedule to meet fixed dates.

- Add resources. The final piece to developing the project schedule

is adding resources. Because the durations have been adjusted, the resources

will be allocated to the tasks with the productivity factor already computed.

After the resources have been added, adjustments will need to be made to address any over- or under-allocations. You want to make sure your team has enough work to fill 40 hours each week.

Building a manageable schedule that accurately reflects the time and personnel needed to complete a project is your huge step toward helping you push back against unrealistic new projects at the end of the year. Part 2 of this series discusses the importance of tracking the progress of the project and how you can use your schedule to communicate resource availability and return unneeded funding earlier in the year. Those funds can be used to start new projects earlier and eliminate the massive pile of unused dollars at the end of the year.

Bonus Section

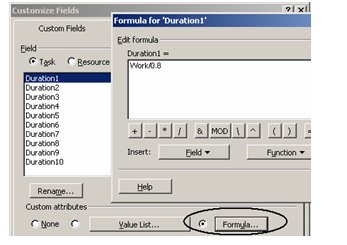

Automating an 80% productivity factor in Microsoft Project can be done using a custom "Duration" field. This will allow you to calculate the time it will take a single resource to accomplish a particular task.

The custom "Duration" field (see figure B) is set up to automatically calculate the number of days a task will take based on the number of hours assigned to it.

This is accomplished by assigning a formula to "Duration1" that divides Work by 0.8 (see figure C). Because Duration fields are measured in days, the result is automatically calculated as days.

You can then copy the "Duration1" column and pasted it into the "Duration" field. A custom field is required because a formula cannot be added to the standard duration field. It is a dynamic field that automatically adjusts during the project. The calculated value is the suggested amount and you should adjust it to match the reality of your project.