Agile Organizational Structure

- Physical Workplace Design

- Organizational Structure

- Heuristics of Agile Organizational Designs

- Summary

- Q&A

- Further Resources

Examples of how to design structure for your Agile organization, including physical workspace and structure, to be more agile. This excerpt covers traditional structures, as well as more emergent ones, and discusses benefits and drawbacks of each.

The tools, techniques, and methods described in the previous chapter can be incredibly powerful to help unlock organizational agility. Yet, their relative effectiveness will be greatly affected by the context within which they are used. One of the influences of that context is Organizational Design. Without an Organizational Design that supports an end-to-end view of value creation, the technology deployed will have limited effect.

In this chapter and throughout this book, I refer to Organizational Design from two perspectives:

The Physical Design of the Workplace: Here, I’m referring to the physical (and sometimes virtual) workspace within which people collaborate, communicate, and work together.

The Organizational Structure of the Organization: Here, I’m referring to the way in which the organization coordinates its people, resources, and assets in an effort to create value in a sustainable manner.

Physical Workplace Design

Research has shown that the way our workplaces are designed has an outsized impact on our productivity, our ability to collaborate, and our engagement in the workplace. We’ll explore this in more detail later. In this section, I outline why the workplace is so important for knowledge work. I also highlight some of the key elements of an effective workspace and provide a case study of how my team completely transformed the workplace at NAVTEQ from a traditional “cubicle farm” to a highly collaborative, energetic place to work. My hope is that this will inspire you to rethink the way you view your own place of work and look for ways to optimize it for human collaboration and communication—not for square footage, as is often the case.

Designing for Great Teams

The least common denominator in an agile enterprise is the team. Although each individual contributes to developing a great product, it is ultimately the team that is necessary and responsible for creating compelling user experiences. Given the importance of teams as an organizational unit, recognizing exactly what makes a team highly productive has been an important area of business research. For those of us who have been fortunate enough to have worked on a high-performing team, it’s sometimes difficult to pinpoint precisely what made that team so productive.

Early in my career, I was fortunate to work as a software engineer on a team that created custom financial forecasting solutions for Hewitt Associates (later acquired by AON), an HR management consulting firm. We were a relatively small team of five people, and we were fiercely proud of the product we created. When our internal customers requested new features, we rarely took more than two weeks to develop, test, and deploy them in production. (This was as close to Continuous Deployment [CD] as we got in the early 2000s.)

Better yet, our internal customers enjoyed using the product. Almost every month, we’d get a note from an end user who’d express how he loved working on RevCast because it was so friendly and different from all the other impersonal systems he had to spend most of their time on every day. Remember, this was an internal forecasting system, not a consumer app; having users reach out to us like this was not common with these types of systems. But the users loved our product—and started talking about it. In fact, RevCast was so successful that when senior management wanted to move RevCast’s functionality to a more established Enterprise Resource Planning ERP system (PeopleSoft), there was a near revolt among the financial analysts who refused to give up the flexibility, intuitiveness, and responsiveness of this home-grown application. RevCast prevailed and became the system of record for more than $1.8 billion worth of business for several years in the early 2000s.

I’ve asked myself many times afterward why the team was so successful. Was it because of the personalities of the people on the team? Did our skills, knowledge, and abilities complement each other particularly well? Was it perhaps an extremely charismatic leader who made it all happen? Or was it simply luck?

The Science Behind High-Performing Teams

Alex Pentland, a director at MIT’s Human Dynamics Laboratory, set out to find out exactly what made teams great through careful observation of more than 2,500 teams in a variety of industries. By using a set of sensors collecting more than 100 data points a minute and observing teams work together for up to six months at a time, he could correlate the way the teams worked with their respective outcomes. He found that what made teams successful was not so much the composition of the teams themselves or the content of what the teams were discussing, but how they were communicating with each other:

“...we’ve found patterns of communication to be the most important predictor of a team’s success. Not only that, but they are as significant as all the other factors—individual intelligence, personality, skill, and the substance of discussions—combined” (Pentland, 2012).1

Specifically, Pentland was able to identify three elements of communication that directly affected the degree to which teams were successful:

Energy: The number and nature of exchanges between team members matters. More exchanges are generally better as long as they are relevant to the task at hand. Face-to-face exchanges are most effective; texting and email were found to be among the least effective forms of communication.

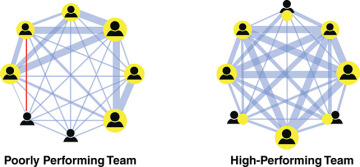

Engagement: The degree to which communication exchanges are distributed among the team members is important (see Figure 4.1). More evenly distributed exchanges are found to be more effective than “clustering,” where representatives of one role only communicate with others having the same role, for instance.

Figure 4.1 Visualization of Communication Patterns on High-Performing Teams vs. Poorly Performing Teams According to Pentland’s Research

Exploration: The degree to which people are engaging with members outside of their core group is critical. Consistently, higher performing teams are engaged more frequently with members outside their own unit—and demonstrate higher levels of creativity and innovation.

Although I could not put my finger on it at the time, the communication patterns identified by Pentland were exactly what I experienced as a team member of RevCast early in my career. Looking back, I remember that people remarked about an audible “buzz” when entering our workspace—we were working together on problems, exchanging ideas, and engaging in active problem solving. We never considered each other’s individual roles as significant—we were merely team members with different things to contribute. And perhaps because of the energy displayed by the team, we constantly had the opportunity to interact with people outside of our own group. These people helped us gain a more comprehensive perspective of the solutions we were building and allowed us to gain empathy with our stakeholders and end users.

Given the insights in Pentland’s study and the obvious benefits that high-performing teams unleash, how can we create a workspace that increases the opportunity for team energy, engagement, and exploration?

Case Study: More Effective Collaboration Spaces at NAVTEQ

When I was leading the agile transformation at NAVTEQ in Chicago, we found that one of the key impediments to effective collaboration between and across teams was lack of an effective work space. Traditional “cubicle land” was simply not cutting it: teams reported that it was difficult to meet with each other on an ad-hoc basis. Pairing was next to impossible and constantly struggling to find available meeting rooms made face-to-face collaboration a challenge.

To alleviate these impediments, executive management supported our proposal to completely redesign our existing workplace. In the next section, I outline how we approached the problem, describe some of the lessons we learned, and provide examples of how the workspace evolved to better serve the needs of our teams.

The Working Agreement: Approach the Workplace from an Agile Perspective

As part of the agile enterprise transformation at NAVTEQ, I was leading the Agile Working Group (AWG), a team tasked with removing impediments to organizational agility. (More on the AWG in Chapter 8, “Building Your Organization’s Agile Working Group.”) We understood that we needed to dramatically change the office landscape, which was currently set up as traditional cubicles. Each person had his own little semi-private space, but this isolation was completely anathema to collaboration. We also understood that we did not know all the answers and that we needed to approach this project with an agile mind-set: we would learn along the way and modify our thinking as we uncovered more information.

We decided to collaborate with a workspace architecture firm. During the process, the architects consulted with us as external resources and provided expertise, ideas, and counsel as we built our agile workplace.

Phase 1: Design Agile Pod Prototypes

The AWG started our efforts by examining the current workspaces and gaining a deeper understanding of the problems the teams were encountering through in-depth interviews with team members, anonymous surveys, and observations from coaching. The themes that kept coming up were “lack of collaboration” and “communication challenges.” Team members needed to work more closely together so they could make quick decisions based on high-bandwidth communication. The existing cubicle design made it difficult to work together effectively without having to schedule separate meeting rooms; however, this added a lot of unnecessary overhead and waste.

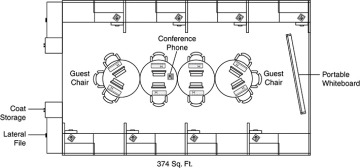

In cooperation with the architecture firm, we created a first set of prototype “Agile pods” designed to help address the problems of collaboration and communication. Figure 4.2 provides an early example of the design. The first set of prototypes was based on a variation of this general scheme.

Figure 4.2 “Agile” Pod Design; Everything Inside the Space Is Moveable, Including Chairs, Tables, Whiteboards, and Video Screens

The design was created with a focus on flexibility, spontaneous collaboration, and the capability to bring in members from other teams on a moment’s notice.

We asked for volunteer teams and set up four separate “experiments” on two different floors. Two of the teams were in 8-person pods, the other two were in 7-person pods. Because our company tried to keep the teams small as a general rule, this setup seemed reasonable: we felt confident we had optimized the work spaces for the factors that teams felt were important.

Phase 2: Run the Experiment—and Reveal Uncommon Learning

The four volunteer teams agreed to participate in the experiment under the following conditions:

The experiment would last no more than three months.

If the team members did not like the collaboration space, we committed to moving them back to their old work environment at the end of the experiment.

We decided that a time-boxed effort was indeed best. That provided employees with the option to go back to the current setup at the end, eliminating the risks involved with trying the new environment. In retrospect, creating this “safe-to-fail” condition was a major reason we were able to get volunteers to sign up for our experiment.

As the teams moved into their new “homes,” we made a special effort to celebrate their involvement publicly, half-jokingly comparing their efforts to the Apollo space mission some decades earlier. I say “half-joking” because we recognized it was no small feat to dramatically change employees’ workspaces in this manner—especially when they could have continued working without any change at all.

Over the next three months, we interacted with the teams in a number of ways, collecting data to better understand the degree to which the agile pods were helping to increase team members’ levels of collaboration, improve their communication patterns, and find new ways of working together. We collected the data by combining a number of sources: observation, surveys, periodic open space events, individual interviews, and objective data. (We even considered placing a time-lapsed video camera in the pod to observe communication patterns in the teams over time, but this was quickly rejected by the teams as if they were “in a zoo.” Point taken.)

The data we collected came back remarkably consistent among the four teams. Unfortunately, it was initially very painful. To our surprise, most participants absolutely hated working in the new pods. They said they were noisy. There was virtually no privacy to make occasional personal calls. One volunteer was pretty clear in her assessment: “This is a hellish working environment; please change whatever you’re doing and rethink the whole agile collaboration concept.” The judgment was pretty clear: if the pods are going to look like this, they would rather quit their jobs than work in this environment!

However, there was some good news: teams were collaborating better. Communications were more effective within and across teams. We noticed there were a few times each week when we could observe the teams really gelling together—a few people from different teams got together for regular Xbox game nights at the office, and ad-hoc table tennis tournaments started popping up. We recognized we were onto something—but we knew we had to change some of the design decisions we made in the prototypes. We needed to amplify all the positive developments we saw related to increased collaboration and cross-team communications and dampen the issues related to noise concerns and lack of privacy.

Phase 3: Back to the Drawing Board—Optimizing for the Right Thing

Running these experiments was incredibly valuable. Without them, we would only have a theoretical idea of what worked and what didn’t. Afterward, we had a vivid understanding of what we needed to change so that we could create a work environment for our people that not only enhanced communication and collaboration, but also respected their individual needs for privacy and focus.

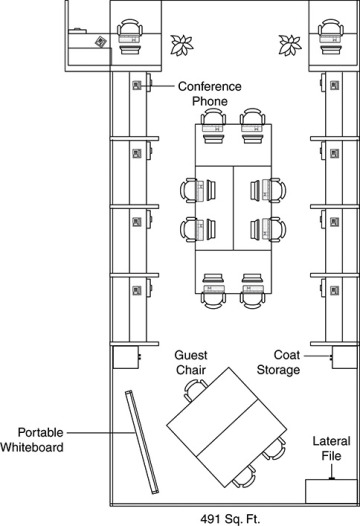

In the end, the changes we needed to make to the pods from the original design were relatively small, but with one significant design difference: size. Our prototype pods reduced the amount of square footage used per employee. Team feedback showed us that to be effective, the pods needed to be bigger, and we needed to provide additional supporting rooms to complement them.

This insight changed the math of the physical workspace design effort: no longer could we argue that we could improve team performance and save on real estate costs. We now had to draw a line in the sand: if we couldn’t have both, which was more important: team performance or square footage?

Upper management was clear that their commitment to the agile transformation was unwavering, and they approved the additional cost incurred by increasing the size of the pods and improving additional areas of privacy for team members.

The new PODs were bigger and provided additional space for “guests.” They also were accompanied by additional privacy spaces that team members could use any time they needed to get out of the “bubble,” focus on something for themselves, or have a private conversation (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Revised “Agile” Pod Design; The Increased Size Provided More Space for Team-Specific Items, Occasional Guests, and Activities Like Pairing

After making these changes and receiving positive feedback from the volunteer teams, we decided to roll out the redesigned PODs across all the teams in our R&D division, ultimately ensuring all of NAVTEQ’s development teams were working in a more collaborative workspace.

What We Learned

Through this experience, we learned a few valuable lessons. Although the research was unequivocal that high-bandwidth communication does improve with a more collaborative workspace, we found that a few practical considerations needed to be considered when designing an agile workplace:

Provide Effective Focus Space: Knowledge workers frequently collaborate and work together, but when deep focus is necessary, they need to be left alone so they can work in peace. This means that a workplace needs to accommodate both a satisfactory noise level and an appropriate amount of privacy. As much as great products are created by teams, individuals also need space to concentrate their efforts when working heads-down on deep problems.

We approached this need by raising the walls of the agile pods to about 6 feet so that the teams could focus without noise interruptions from other teams. We found that “noise” coming from people working on the same project was not disruptive; conversations regarding work that had nothing to do with the current work was.

In addition, we installed a number of “privacy booths” outside the agile pods. These could be used by anyone at any time, without scheduling. This made it possible to have spur-of-the moment private conversations with a spouse, for example, or a space to focus on deep problem solving for a few hours.

Create Opportunities for Collaboration Without Sacrificing Focus: Pentland’s research shows us that successful teams collaborate with members outside their own core units, but the places where collaboration happens can vary. Designing to include more public spaces can create meaningful collaboration opportunities.

Steve Jobs famously made sure the bathrooms at Pixar’s offices were set up in such a way as to increase opportunities for “serendipitous personal encounters.” He believed that having people from different and diverse teams meet each other under unplanned circumstances helped spur innovation, inspiration, and creativity.2

Support Effectiveness Through Flexible Options: Although we recognize that face-to-face conversations are superior methods of communication, knowledge workers value workplace flexibility above all else. Given the distributed nature of workers today, it is important to build flexibility into the design of the workplace. This means that the office space itself needs to be malleable and open to virtual communication technologies.

For instance, Intel has built co-working spaces throughout its campuses worldwide so that people can just as easily work in semipublic spaces bustling with colleagues as they can in private, two-person task rooms. Having options allows for flexibility. People can enjoy the buzz of a creative space when needed and take advantage of solitude when deep concentration is more appropriate. The key element of this workplace design strategy is choice: employees get to choose which environment they want to work in based on their personal work needs and the specific nature of the work itself. One size does not fit all.

This flexibility extends to another option: not working in the office at all. Working remotely is becoming increasingly more important, especially in tech. Remote work is a key enabler to gaining access to the very best talent, regardless of where they reside in the world. In light of this, some companies are choosing to go completely virtual, with people working from all corners of the world and coming together in virtual meeting rooms on a regular basis.

Although I’ll argue nothing beats face-to-face communication, the reality of today’s distributed organizations is that this is not always practical. I’ve found virtual teams to be quite effective—as long as the technical infrastructure enables seamless information exchanges and you allow for periodic face-to-face interactions on a regular cadence.

True, your travel budget is likely to be affected when having a highly distributed team; creating a high-performing virtual team isn’t free. I’ve found that coming together on a regular cadence—ideally, every 3–4 months—is essential to creating the type of mental alignment Appelo refers to in the preceding sidebar. (For more ideas on how to support virtual workplaces, check out the companion website: www.unlockingagility.com/.)

The Human Impact of Effective Workspaces

The co-location effort at NAVTEQ was a significant success. In less than six months after the teams had moved into their new workspaces, defects in production were down by more than 60%. The time it took to complete critical issues improved 2.5 times, and teams were delivering with more predictability and confidence.

Perhaps most important of all was the fact that our employee engagement scores increased. Although there were a few adjustments made along the way (additional footrests, mini-fridges, Xboxes for sporadic team building, and so on), the general consensus among our employees was that this was a huge improvement and that working together was easier and more—dare I say it?—fun.

For me, the most meaningful proof of our success was reflected in an exchange I had with one of our top engineers, Kevin. A few months after the office redesign, he took me aside, smiling, to share some exciting personal news: he had received an offer from Google.

I wasn’t sure how to feel. I was happy for Kevin; Google was a great opportunity. But I was also profoundly sad that we would be losing one of our best engineers, someone I cared about a great deal. I managed to respond with something that must have resembled a combination of a frown and a smile.

“I turned them down,” Kevin said. He looked at me and smiled even wider. It took me a few seconds to realize what he’d just told me: he’d turned down Google to stay with us. “I realized I don’t want to leave this place. I love my team, we’re working on really amazing stuff, and I want to be part of this journey we’re on!”

In that moment, it became clear to me what an impact organizing the workspace had made to our people. By designing a workspace that took into account what our people were telling us and recognizing the patterns inherent in effective communication and collaboration, we had made NAVTEQ a better place to work. This was not about moving a few tables around and adding some plastic flowers to improve office optics. This was real. It was substantial. And it was meaningful. Did creating this agile working space cause higher performance and a better working environment? I can’t prove that there was a causal relationship—and it’s likely that there were many other factors contributing to improving work at NAVTEQ. But was it one factor contributing to having one of our top engineers choose to stay with us and being part of our journey? Of that, I have no doubt.

I gave Kevin a warm hug, unable to speak a single word.